Art Stories in the Middle Ages

The Middle Ages are still associated mainly with violence and obscurantism, but it is unfair to reduce it to that: in this period precious works were produced, some of them part of the collection of Calouste Gulbenkian.

It is not uncommon to see the Middle Ages referred to as the Dark Ages. Particularly in popular culture, this period of history continues to be associated with violence and obscurantism. But this is an unfair association – or a generalization, if you like –: the Middle Ages spans from the 5th to the 15th century, between the falls of the Western and Eastern Roman Empires. In that time period, much has passed. And not everything was violent or dark.

It is true that the great migrations, also called “barbarian invasions”, which began the Middle Ages, led to a phenomenon of ruralization, coinciding with the decline of cities, the retraction of trade and the degradation of large public structures such as roads, bridges and aqueducts.

But it didn't have to wait for the 15th century for there to be a renaissance – not to be confused with the Renaissance. There were even several revivals of the importance of cities from the 11th century onwards, when the first European universities began to emerge: Bologna in 1088, Paris around 1150, Oxford in 1167, Salamanca in 1218 and Coimbra in 1288.

When contemplating the art produced in the Middle Ages, the aforementioned generalization loses even more meaning. It is, for example, from the century. XIII the precious parchment of the Apocalypse, where gold and silver leaf is used, and tempera painting on parchment. It is one of only three examples that were executed in England between 1260 and 1275. It was part of the estate of the important British collector Henry Yates Thompson and was acquired by Calouste Gulbenkian in 1920.

Another work from the Founder's Collection of the Calouste Gulbenkian Museum that dates back to the Middle Ages is the Book of Hours of Margarida de Cleves, from 1395-1400. This type of book was intended for private worship, with texts illustrated by full-page miniatures. This stands out for including a representation of Margaret of Cleves herself, wife of Duke Albert of Bavaria, in prayer before the Virgin and Child, thus establishing a rare link between the profane and the divine world.

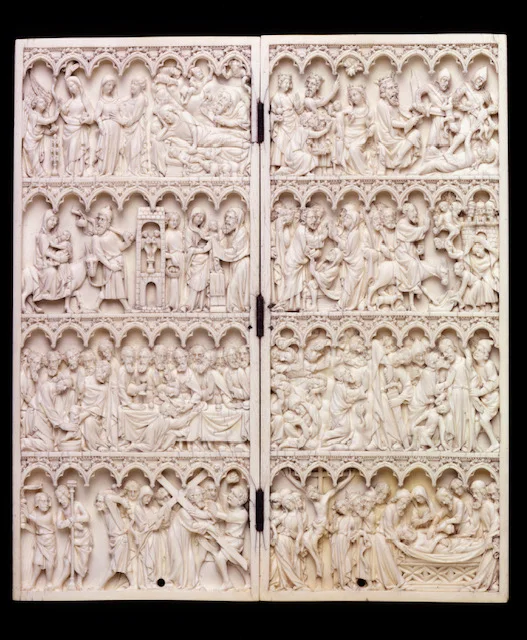

Religious art was the one that best survived the passage of time and political transformations. It had, at the time, a function greater than serving as a reflection or celebration: it was an agent of history, teaching the doctrine through images. An example of this is another work in the Collection, this one acquired by Gulbenkian in Paris in 1918: it is a diptych in ivory leaves with scenes from the Passion of Christ that had a catechetical function: it is equivalent, in essence, to a small book illustrated, such is the detail and refinement with which it was executed.

Diptych with Scenes from the Life and Passion of Christ. Paris, c. 1350-1375. Ivory. Calouste Gulbenkian Museum. Photo – Catarina Gomes Ferreira

The use of ivory also reveals that, contrary to what many people think, Europe was not closed in on itself during this period. On the contrary, it always maintained commercial, religious, diplomatic and military contacts with the peoples of the Mediterranean and even the Far East. Not only did goods arrive from these parts of the continent, but also reports from travelers – such as Marco Polo – who spread different ideas and cultural habits.

The revival of the Middle Ages took place in the 19th century, at the time of the industrial revolution and the liberal revolution, in which the Gothic style was recovered and revalued through the restoration of some of the great medieval monuments in Europe – here the action of some artists and architects of the time such as the French Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, William Morris or the Catalan Antoni Gaudí.

Even today, it is common to find reproductions of the rich medieval imagery in cinema and literature, the most flagrant and mediatic examples being the Lord of the Rings and Game of Thrones sagas. That is, yes, there was a lot of violence and obscurantism in the Middle Ages, but as art proves, there was also much more than that.

- April 17, 2025

Gallery Of Humor Drawing By Swaha - France

- April 17, 2025

Gallery Of Graphic Design By Gerard Alsteens - Belgium

- April 17, 2025

Gallery Of Graphic Design By Kazem Bokaei - Iran

- April 17, 2025

12 Houses with Art Studios in Latin America

- April 16, 2025

Honduran Artist's Exhibition Attracts Art

- April 17, 2025

12 Houses with Art Studios in Latin Ame…

- April 16, 2025

Famous 20th-Century Painters and Their …

- April 14, 2025

Analysis of Artistic Works Created with…

- April 13, 2025

From Digital Art to Contemporary Art

- April 13, 2025

The Expansion of Photography

- April 12, 2025

When is photography considered art?

- April 10, 2025

Impact of AI on the Diversity of Artist…

- April 10, 2025

How can AI enhance artistic creativity?

- April 09, 2025

The Impact of Artificial Intelligence o…

- April 08, 2025

Latin American art, a goldmine of oppor…

- April 07, 2025

Contemporary Art in Brazil: Between the…

- April 07, 2025

Mexican Muralism: Art for the People

- April 06, 2025

History of graphic art in Brazil

- April 05, 2025

Modern Art: A Renaissance in Art History

- April 02, 2025

Aldo Estrada (Ilustronauta): From Peruv…

- March 31, 2025

How ChatGPT is Turning Photos into Japa…

- March 30, 2025

Arístides Hernández (ARES): A Sharp Min…

- March 30, 2025

The Masters of Cuban Caricature: Celebr…

- March 29, 2025

Where Will Artificial Intelligence Take…

- March 27, 2025

A Few Fascinating Features of Latin Ame…

- August 29, 2023

The history of Bolivian art

- February 19, 2024

Analysis and meaning of Van Gogh's Star…

- January 28, 2024

Culture and Art in Argentina

- September 25, 2023

What is the importance of art in human …

- September 23, 2023

What is paint?

- August 10, 2023

14 questions and answers about the art …

- August 30, 2023

First artistic manifestations

- August 23, 2023

The 11 types of art and their meanings

- March 26, 2024

The importance of technology in art1

- August 16, 2023

The 15 greatest painters in art history

- September 23, 2023

History of painting

- April 06, 2024

History of visual arts in Ecuador

- January 20, 2024

What is the relationship between art an…

- January 31, 2024

Examples of Street Art – Urban Art

- March 26, 2024

Cultural identity and its impact on art…

- September 23, 2023

Painting characteristics

- April 07, 2024

Graffiti in Latin American culture

- October 21, 2023

Contemporary art after the Second World…

- August 25, 2024

A Comprehensive Analysis of the Cartoon…

- March 05, 2024

The art of sculpture in Latin America

- February 19, 2024

Analysis and meaning of Van Gogh's Star…

- August 13, 2023

9 Latino painters and their great contr…

- August 29, 2023

The history of Bolivian art

- August 10, 2023

14 questions and answers about the art …

- January 28, 2024

Culture and Art in Argentina

- August 23, 2023

The 11 types of art and their meanings

- November 06, 2023

5 Latin American artists and their works

- September 23, 2023

Painting characteristics

- August 27, 2023

15 main works of Van Gogh

- September 23, 2023

What is paint?

- September 25, 2023

What is the importance of art in human …

- August 30, 2023

First artistic manifestations

- January 20, 2024

What is the relationship between art an…

- December 18, 2023

10 iconic works by Oscar Niemeyer, geni…

- January 12, 2024

10 most beautiful statues and sculpture…

- October 30, 2023

Characteristics of Contemporary Art

- March 26, 2024

Cultural identity and its impact on art…

- August 22, 2023

What are Plastic Arts?

- April 16, 2024

The most important painters of Latin Am…

- October 11, 2023