The mystery of the hidden banner in 'Manifestation', the iconic painting by Antonio Berni

The researchers who studied the work, a key to political and social art in Argentina, suspect that the artist sketched a poster that he discarded in the final version of 1934.

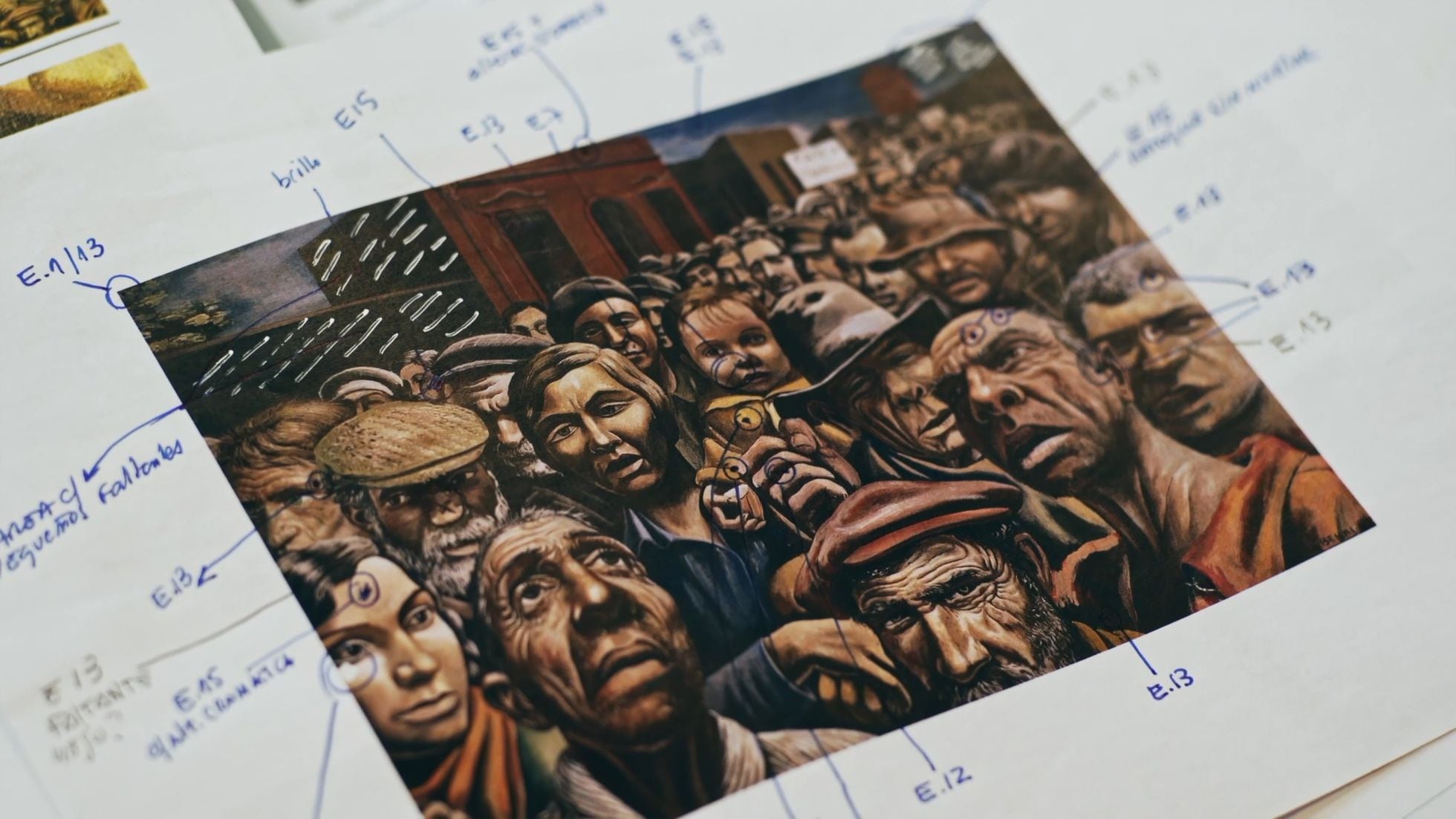

The clues were plain to see: a man's raised fist in the center of the painting and a woman's clenched hand in the lower left corner of the painting. The interpretations of the experts who have studied the Manifestation painting, by Antonio Berni, until now pointed out that the first fist symbolizes the strength of that working mass painted by the Argentine artist, while the second is part of "little strange compositional issues" that has the work. But a series of analyzes have revealed the possibility that those closed hands are actually there to hold up a large white sign that the creator painted and eventually concealed under more layers of paint.

The painting, a key work of political and social art in Argentina, has always been analyzed from a historical perspective. Painted after Berni's return from Paris, it is among his emblematic paintings of New Realism and shows, in the foreground, the anguished faces of the workers demonstrating en masse. Studies such as those carried out now by experts from the Museum of Latin American Art of Buenos Aires (Malba) and the University of San Martín had not been applied to this work. The analyzes culminated in 2022 and in August Malba launched an online multimedia project, Manifestación en foco, to disseminate the results obtained after analyzing the material aspects of the work with different techniques.

The specialists wanted to know, for example, what pigments and binders Berni used. It had always been believed that the artist emulsified his pigments with egg, but analysis indicated that he may have done so with animal glue. They also wondered what his work methodology was and discovered that, in the case of Manifestación, Berni first painted a white base, then drew directly on the canvas with charcoal and finally began to give the layers of color. They did not find any sketches of the work, but they were able to identify some of the changes that the artist made during the execution, which were few.

"We thought we had seen all the modifications we were going to see until this great find began to appear," Valeria Intrieri, responsible for managing the Malba collections, told EL PAÍS. The banner, she says, was a "surprise" that came from an X-ray. “He raised it as a very large poster that crosses a large part of the work. There were some indications”, says Intrieri, referring to the fists of those two characters who have their hands closed without holding anything in the final work. "If we look at it now, it was obvious that there had to be something," she says. “What we couldn't find was an inscription,” she says.

Hypothesis about a slogan

Malba researchers are still wondering if there was a message on the banner. Current technology does not show that there has been one, but they do not rule out that in the future the equipment will allow us to see details that are not visible now. The work, in its final version, has a single legible slogan, which calls for "bread and work", and two faded banners in the background of the work. After the crisis of 1929, unemployment and mobilizations were widespread in the world.

The art historian Roberto Amigo, one of the greatest experts on Berni's work, does not believe that there is a text by the artist on the poster raised in the initial composition. However, he proposes hypotheses about what the slogan could have said. "One option is that the banner is an opposition to the Eucharistic Congress, which is central to the discussion at that time," says the researcher. But Amigo chooses to believe that the message may have been related to the post-war hunger marches.

"The clues give us very general orders, such as a demand for work and bread or a call for a general strike," explains the historian, and rules out other options. "I don't think it was a banner of direct reference to the Argentine communist party because at that time the party itself was making a self-criticism of its failure to conquer the proletariat," Amigo maintains. Afterwards he continues: “We cannot see the possibility that he aimed at a class alliance in the fight against fascism because it was not the position of the party in 34″.

The historian points out that Berni's decision to eliminate the cartel was “very early”. With the banner, he says, "the compositional reading would have been different." “The banner would have annulled the perspective that the work has, would have mitigated the helplessness of those faces and would have determined a reading”, he explains. Friend believes that Berni deleted it "because any message posted there was extremely circumstantial": "Not knowing what message or slogan the banner could carry is what allows the power of the painting at different times."

- April 16, 2025

Honduran Artist's Exhibition Attracts Art

- April 16, 2025

Festivals Celebrating Latin Music

- April 16, 2025

Gallery Of Humor Drawing By Yassin Alkhalil - Syria

- April 16, 2025

Gallery Of Illustration By Chris Madden - USA

- April 16, 2025

Gallery Of Illustration By Rancesco Chiappara - Italy

- April 16, 2025

Famous 20th-Century Painters and Their …

- April 14, 2025

Analysis of Artistic Works Created with…

- April 13, 2025

From Digital Art to Contemporary Art

- April 13, 2025

The Expansion of Photography

- April 12, 2025

When is photography considered art?

- April 10, 2025

Impact of AI on the Diversity of Artist…

- April 10, 2025

How can AI enhance artistic creativity?

- April 09, 2025

The Impact of Artificial Intelligence o…

- April 08, 2025

Latin American art, a goldmine of oppor…

- April 07, 2025

Contemporary Art in Brazil: Between the…

- April 07, 2025

Mexican Muralism: Art for the People

- April 06, 2025

History of graphic art in Brazil

- April 05, 2025

Modern Art: A Renaissance in Art History

- April 02, 2025

Aldo Estrada (Ilustronauta): From Peruv…

- March 31, 2025

How ChatGPT is Turning Photos into Japa…

- March 30, 2025

Arístides Hernández (ARES): A Sharp Min…

- March 30, 2025

The Masters of Cuban Caricature: Celebr…

- March 29, 2025

Where Will Artificial Intelligence Take…

- March 27, 2025

A Few Fascinating Features of Latin Ame…

- March 27, 2025

9 Key Books to Understand Latin America…

- August 29, 2023

The history of Bolivian art

- February 19, 2024

Analysis and meaning of Van Gogh's Star…

- January 28, 2024

Culture and Art in Argentina

- September 25, 2023

What is the importance of art in human …

- September 23, 2023

What is paint?

- August 10, 2023

14 questions and answers about the art …

- August 30, 2023

First artistic manifestations

- August 23, 2023

The 11 types of art and their meanings

- August 16, 2023

The 15 greatest painters in art history

- March 26, 2024

The importance of technology in art1

- April 06, 2024

History of visual arts in Ecuador

- September 23, 2023

History of painting

- March 26, 2024

Cultural identity and its impact on art…

- January 31, 2024

Examples of Street Art – Urban Art

- January 20, 2024

What is the relationship between art an…

- April 07, 2024

Graffiti in Latin American culture

- October 21, 2023

Contemporary art after the Second World…

- August 25, 2024

A Comprehensive Analysis of the Cartoon…

- September 23, 2023

Painting characteristics

- January 12, 2024

10 most beautiful statues and sculpture…

- February 19, 2024

Analysis and meaning of Van Gogh's Star…

- August 13, 2023

9 Latino painters and their great contr…

- August 29, 2023

The history of Bolivian art

- August 10, 2023

14 questions and answers about the art …

- January 28, 2024

Culture and Art in Argentina

- August 23, 2023

The 11 types of art and their meanings

- November 06, 2023

5 Latin American artists and their works

- September 23, 2023

Painting characteristics

- August 27, 2023

15 main works of Van Gogh

- September 23, 2023

What is paint?

- September 25, 2023

What is the importance of art in human …

- August 30, 2023

First artistic manifestations

- January 20, 2024

What is the relationship between art an…

- December 18, 2023

10 iconic works by Oscar Niemeyer, geni…

- January 12, 2024

10 most beautiful statues and sculpture…

- October 30, 2023

Characteristics of Contemporary Art

- March 26, 2024

Cultural identity and its impact on art…

- August 22, 2023

What are Plastic Arts?

- April 16, 2024

The most important painters of Latin Am…

- October 11, 2023