Artists who transformed Contemporary Art in Latin America 1

Artists who transformed Contemporary Art in Latin America 1

In Latin America, the period between the early 1960s and the late 1980s was marked by authoritarian regimes, extreme inequality, systematic violence, social movements, and repression of the population. But also, it was a period where women manifested their radicality through various plastic languages, exploring the political dimension of their bodies, experimenting conceptually and aesthetically, and organizing themselves into collectivities that transformed art in this region.

Although the historical and creative contexts are specific for each country, we made this selection - insufficient to understand the importance that hundreds of women had in the construction of these other stories of art history - considering that several authors locate the changes in the languages and iconographies that give rise to what we understand as contemporary art, in the sixties. As a reference there is also the extensive historiographic research with a gender perspective that was the exhibition Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960–1985 (2017) at the Hammer Museum, curated by Cecilia Fajardo-Hill and Andrea Giunta. An exhibition that assumed the commitment to bring into dialogue works by 120 Latin American, Latina and Chicana artists who had been partially invisible but indisputably important to understanding the history and present of art in our countries.

Lygia Pape

Brazil (1927-2004)

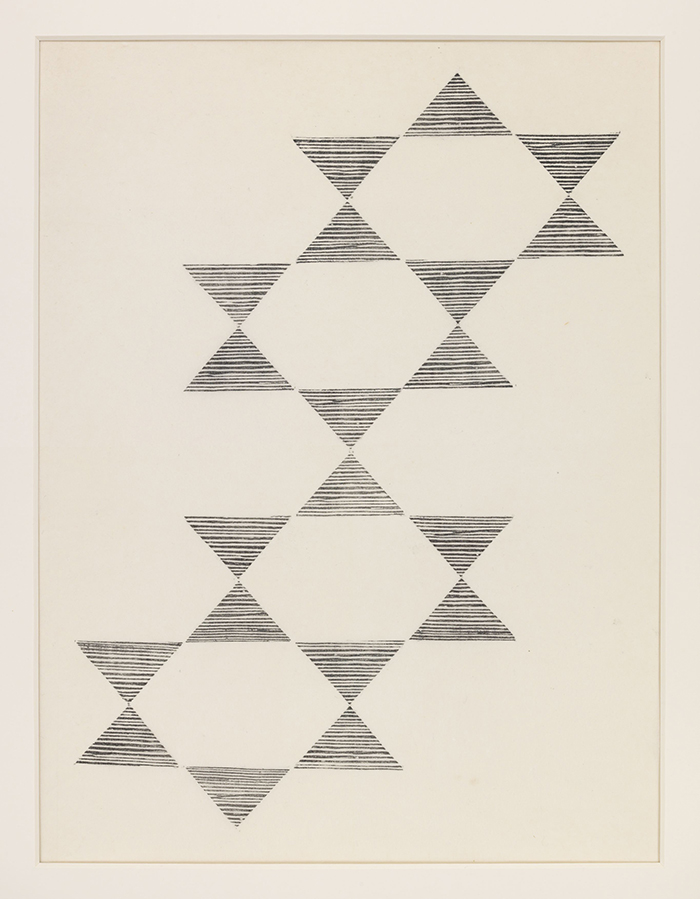

A representative of the neo-concrete movement during the 1950s and 1960s, Lygia Pape systematically built her practice by challenging the principles of geometric abstraction on which concrete art was based to move towards a more organic expression. In her first Desenhos, the geometric shapes recall musical staves, where the visual rhythms of lines, grids and breaks become compositions. In Tecelares, she reinterprets the xylographic process, leaving aside the notion of the multiple to create individual works of art, where the rhythms of reflection, duplication and negative space interact to activate surfaces. Her Books of Creation, Architecture and Time and her iconic Ttéias installations synthesize her artistic process; the latter, as immersive environments defined by geometric distributions of silver and gold threads suspended from the floor to the ceiling and corners of the room.

Zilia Sanchez

Cuba (1926)

«Why do I continue doing works?» Zilia Sánchez once asked. «Well because I need it. “I take it with me,” she replied. Born in Cuba, she decided to live in New York in 1962 and then move to Puerto Rico in 1972. It is there that she begins a series of paintings where she experiments with the figurative elements of the female body and the formal language of abstraction. The warmth and eroticism of the silhouettes on her canvases, which she named with suggestive phrases such as Erotic Topology, broke with the cold and impersonal approach associated with abstraction in Latin America. In Troyanas, she repeats shapes to create a greater sense of duplication and uses visual dualism to establish a sense of what she calls aesthetic balance. Her works have always been attentive to the female experience, honoring the lives and bodies of women, including hers.

Marisol Escobar

Venezuela (1930–2016)

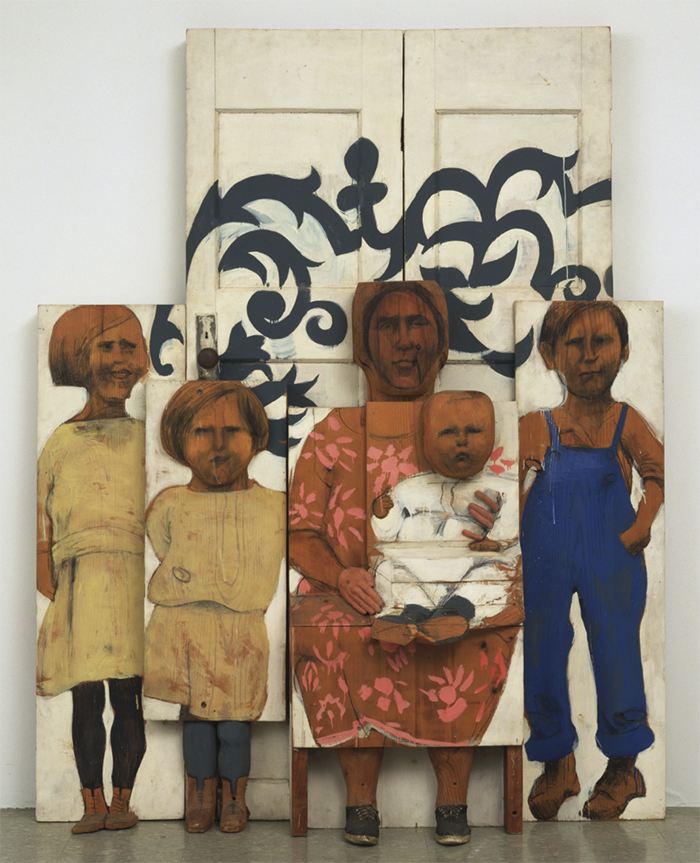

Marisol Escobar spent her childhood following her parents on their travels and her artistic training was irregular, eclectic, academic and largely self-taught. Her early years were marked by abstract expressionism, but she soon preferred sculpture to painting and her particular way of working with materials, especially wood, and later plaster, objects and electricity. By the late 1960s, her style and her reputation were established, and although her personal life associated her with the Pop Art movement, her work was truly outside of any formal legacy. That was the most disturbing and also the most interesting. Her sculptures seemed close to medieval column statues, Native American totem poles, and Hofmann's glued, painted, or sculpted heads; where the hands, the only signs of expression of these lifeless masks lined up, were a reflection of voluntary loneliness.

- December 23, 2025

Negative Space | Oscar Nominated Stop-Motion Animation Short Film

- December 23, 2025

Gaza's harsh winter..

- December 23, 2025

Space Drawing Perspective by Dongho Kim

- December 23, 2025

Victor Moriyama - Brazil

- December 23, 2025

Urban Art in Latin America

- December 23, 2025

Folk Art in Indigenous Communities of Latin America

- December 22, 2025

MACA Inaugurates Exhibitions of Fontana and Uruguayan Modern Art

- December 22, 2025

Graffiti as a Social and Political Language

- December 22, 2025

Graffiti – From the Street to Contemporary Art

- December 23, 2025

Urban Art in Latin America

- December 23, 2025

Folk Art in Indigenous Communities of L…

- December 22, 2025

Graffiti as a Social and Political Lang…

- December 22, 2025

Graffiti – From the Street to Contempor…

- December 21, 2025

Contemporary Art and New Visual Narrati…

- December 21, 2025

Latin American Visual Art as a Space of…

- December 20, 2025

Painting in the Americas: Origins and E…

- December 20, 2025

Key Latin American Artists in the Anti-…

- December 18, 2025

Artistic Movements and Expressions of R…

- December 18, 2025

Art and Anti-Imperialism in Latin Ameri…

- December 17, 2025

Visual Art in El Salvador: Between Memo…

- December 17, 2025

Visual Art in Cuba: A Window to Identit…

- December 16, 2025

Visual Art in Colombia: Diversity, Memo…

- December 16, 2025

Visual Art in Venezuela: Modernity, Ide…

- December 15, 2025

Visual Art in Paraguay: Tradition, Memo…

- December 14, 2025

Visual Art in Chile: Memory, Critique, …

- December 14, 2025

Visual Art in Bolivia: Ancestry, Resist…

- December 13, 2025

Visual Art in Peru: Ancestral Tradition…

- December 13, 2025

Visual Art in Argentina: Identity, Memo…

- December 11, 2025

The Visual Arts in Mexico: Between Myth…

- August 29, 2023

The history of Bolivian art

- February 19, 2024

Analysis and meaning of Van Gogh's Star…

- January 28, 2024

Culture and Art in Argentina

- September 25, 2023

What is the importance of art in human …

- September 23, 2023

What is paint?

- August 23, 2023

The 11 types of art and their meanings

- August 10, 2023

14 questions and answers about the art …

- September 23, 2023

Painting characteristics

- August 30, 2023

First artistic manifestations

- January 12, 2024

10 most beautiful statues and sculpture…

- September 23, 2023

History of painting

- March 26, 2024

The importance of technology in art1

- July 13, 2024

The impact of artificial intelligence o…

- March 26, 2024

Cultural identity and its impact on art…

- April 07, 2024

Graffiti in Latin American culture

- April 02, 2024

History visual arts in Brazil

- August 16, 2023

The 15 greatest painters in art history

- April 06, 2024

History of visual arts in Ecuador

- October 18, 2023

History of sculpture

- November 21, 2024

The Role of Visual Arts in Society

- February 19, 2024

Analysis and meaning of Van Gogh's Star…

- August 13, 2023

9 Latino painters and their great contr…

- August 23, 2023

The 11 types of art and their meanings

- August 10, 2023

14 questions and answers about the art …

- August 27, 2023

15 main works of Van Gogh

- August 29, 2023

The history of Bolivian art

- January 28, 2024

Culture and Art in Argentina

- November 06, 2023

5 Latin American artists and their works

- September 23, 2023

Painting characteristics

- September 23, 2023

What is paint?

- September 25, 2023

What is the importance of art in human …

- March 26, 2024

Cultural identity and its impact on art…

- August 30, 2023

First artistic manifestations

- December 18, 2023

10 iconic works by Oscar Niemeyer, geni…

- January 20, 2024

What is the relationship between art an…

- January 12, 2024

10 most beautiful statues and sculpture…

- August 24, 2023

The most famous image of Ernesto "Che" …

- October 30, 2023

Characteristics of Contemporary Art

- May 26, 2024

Técnicas de artes visuais

- August 22, 2023